I am Hungry only for Silence

A Conversation with Time

I’ve been contemplating the idea of time. What does it really mean when we say we don’t have time? Or that time passes? Or that something is timeless?

The word time comes from Old English tīma, meaning a season or appointed period. It shares roots with Old Norse tímiand Old High German zīmō, and goes further back to an ancient Indo-European root meaning to divide, to cut. Even in its origin, time is about separation—carving experience into before and after. (Oxford University Press, n.d.).

Philosophers, mystics, and scientists have all tried to define it. Aristotle called time the measure of movement. Newton believed it was absolute. Einstein showed us it was relative. Indigenous worldviews describe time as cyclical and land-based. Christian mystics spoke of kairos—sacred time, outside the clock. And psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion saw time not just as an external measurement, but as something that bends inward, shaped by memory, dream, and emotional truth.

But maybe poets say it best: Time isn’t linear. Time is a rhythm. A space. A presence.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about this—how time might also be the space of the heart, a place where something unnamed begins to stir when we are quiet enough to hear it.

And then, I set the question aside, sensing I needed to wait.

Milano, an Unexpected Door Opens

That moment returned, quietly, in Milano.

My husband and I are visiting the city, and I felt a gentle pull to visit Spazio Alda Merini, the house-museum of the poet. We were tired, and I knew the space closed at 7 PM. But something in me insisted: go anyway. Even if we could only see it from the outside, it felt like a kind of pilgrimage.

We took the tram to the Navigli Canal neighborhood, where Merini once lived and wrote. We arrived at Via Magolfa 30 just after 7. I paused to take a photo.

That’s when my husband turned to me and said, “Come—they’re open.”

Two men inside smiled and gestured toward the stairs. “There’s a poetry event starting upstairs in 8 minutes,” one said. “You’re welcome to join.”

And so, without knowing what we were stepping into, we climbed the narrow staircase and entered a softly lit room. Chairs. Books. A quiet hum of expectancy. And then the evening began.

Ida Travi and the Poetics of Time

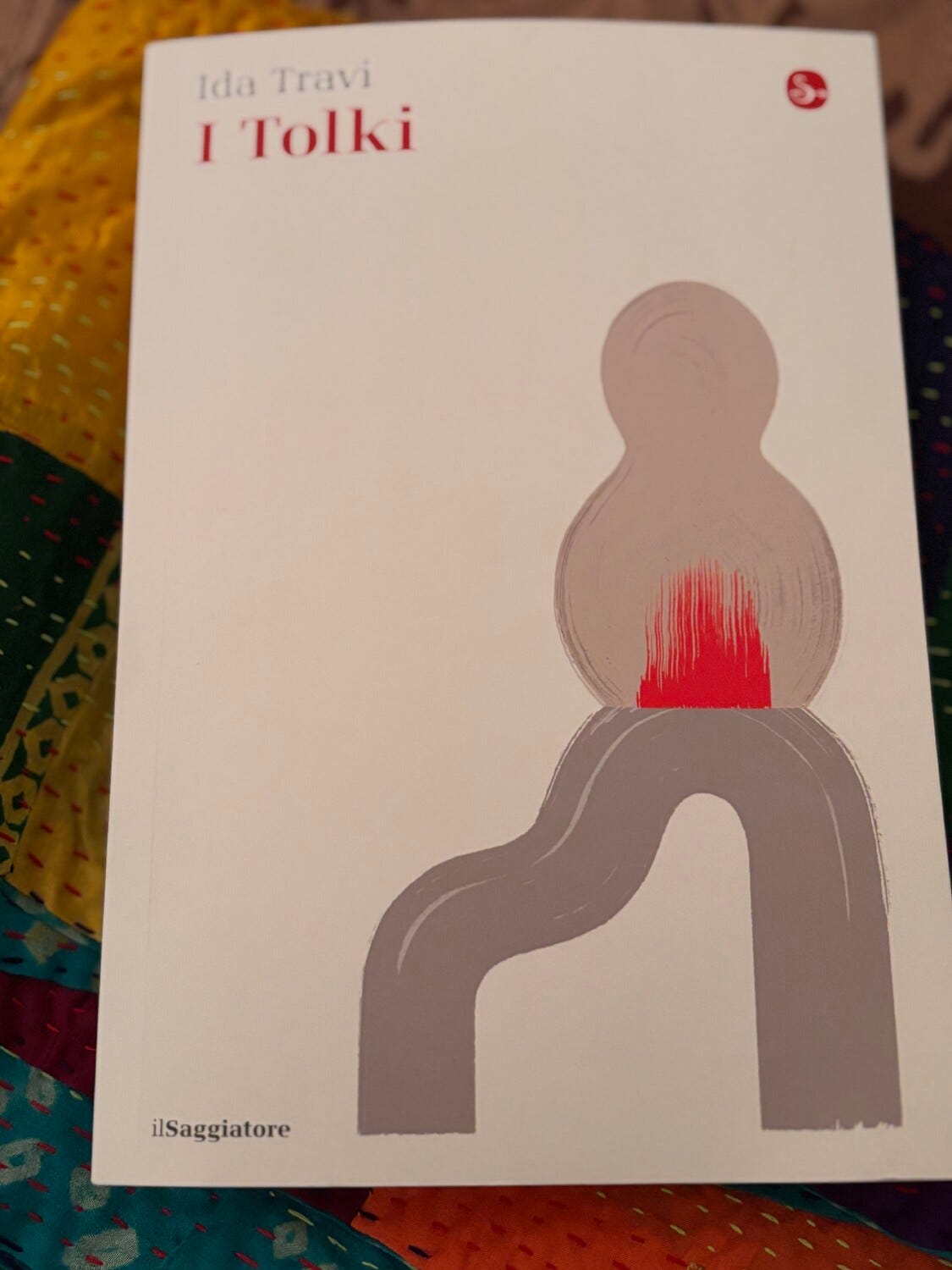

The event featured Italian poet Ida Travi, who had just published I Tolki, a poetic work written in eight parts over thirteen years. Donatella, the artistic director, opened the evening and spoke of Ida’s work in relationship to Alda Merini, connecting two voices of feminine depth and lyrical defiance.

Then Ida stood.

Her voice was not performative—it was present. She didn’t recite her poems; she lived them. There was a rhythm in her delivery that felt ancient and rooted, like she was pulling each word from the silence beneath language.

She later explained her form: poesia del basso continuo—poetry of the low, continuous ground tone. A form that rises not from abstract ideas, but from the earth, from everyday life, from the edges of society. It speaks of what is ordinary and invisible and gives it back to the sacred.

And then she said it:

“This book has been an exploration of time.”

In that moment, tears began falling down my face.

She was speaking directly to the question I had been holding, the one I had set down weeks ago. It felt as though this moment, in this city, in this house of poetry, had arrived just for me.

This was the right time. Not just for her to speak, but for me to listen. Not for her book to be published, but for my question to find its echo. This was not linear time. This was kairos—sacred time. This was the space of the heart.

Ida continued, speaking of those who live on the margins, who feel time differently. She spoke of 'senso della durata'—the sense of duration. How, when you live slowly, or live through silence, or wait for something deep to rise, time moves in strange and beautiful ways.

Then she offered this:

“La poesia tiene aperto il tempo. Non finisce e non comincia.” Poetry keeps time open. It does not end or begin.

It wasn’t just a statement about writing. It was a way of being.

Because poetry, at its essence, doesn’t close things—it holds them open. It makes room for what’s unresolved. It invites us to dwell on what we do not yet understand. It does not rush. It waits. It listens.

Leonardo’s Slowness and Sacred Creation

Earlier that morning, we had stood before Leonardo da Vinci’s Ultima Cena- Last Supper, and heard from our guide how Leonardo was considered “slow.”

He left Florence because he could not create at the speed required by commissions. He needed time to observe, to feel, to deepen. In Milano, under Duke Ludovico Sforza, he found space. He created slowly. He followed the rhythm of his own timing.

And in that time, he made a masterpiece.

Alda Merini: The Lineage of Sacred Time

And now, in this upstairs room, I saw clearly that Ida, too, had followed that sacred rhythm. She had protected her process. She had waited, until the work was whole. Until the time was right.

And Alda Merini—this was her city, her street, her echo in the walls.

She, too, had written from silence, from madness, from grief, from love. Her poetry was not tidy—it was necessary. It was how she survived. It was how she touched the divine.

Ida and Alda were not just connected by geography or genre. They were part of the same lineage: Women who wrote not from urgency, but from fire. Women who gave their silence shape. Women who trusted the deep time of truth.

And as I stepped out into the night, I carried Merini’s voice with me. Not loud. Not declared. Just whispered, from somewhere deep:

“Ho fame di solo silenzio.” I am hungry only for silence. —Alda Merini

Now I understand.

That hunger is not a lack. It's the space in the complex spectrum of time and vignettes of beings. It’s the part of us that longs for something slower, deeper, and more real than the world often allows.

And this night, in the house of a poet, I fed that hunger. With silence. With slowness. With poetry. With time.

What I Am Learning About Time

My question will continue to emerge. At this moment time is not something I must chase. It is something I can enter. Like a room. Like a rhythm. Like a question, I don’t need to rush to answer.

There are times to wait. Times to act. And times to know that waiting is the act.

The deeper rhythm—the one that carried Leonardo, Ida, and Alda—is still available. But it asks us to listen. To honor the fire. To protect the silence. To let the poem become the doorway we walk through.

And always, to remember:

Poetry keeps time open.

Leadership Apothecary Practice: Attuning to the Time That’s Yours

Ingredients:

A quiet moment

A journal, or simply your breath

A memory of something that arrived slowly but changed you

A quote from Alda Merini to hold close:

“Ho fame di solo silenzio.” I am hungry only for silence. —Alda Merini

Practice: Find a still place. Close your eyes. Breathe. Ask:

What kind of time am I in right now? Is this a season of blooming? Listening? Protecting the work still becoming?

Let your body answer before your thoughts do.

Then ask: What in my life needs more space—not to be solved, but to be held open?

Write a sentence to name your rhythm. Return to it when urgency tries to override your knowing. Let it be your basso continuo—the low, steady hum beneath your becoming.

Reference:

Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Time, n., int., & conj., Etymology. In Oxford English dictionary. Retrieved April 4, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7938492889